Earlier this month, I participated in a fantastic digital engagement initiative: #BreakForArt, an hour-long Twitter conversation facilitated by The Phillips Collection and held the first Monday of every month at 1pm EST.

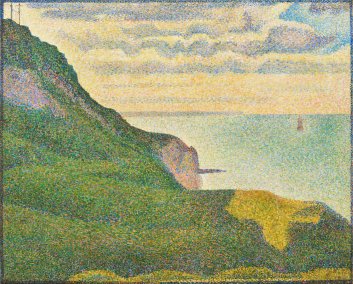

This month, #BreakForArt was jointly hosted by The Phillips Collection and the National Gallery of Art and the topic was Seurat’s Seascape at Pont-de-Bessin, Normandy. The work (pictured below) normally resides at the National Gallery of Art, but is currently on display at The Phillips Collection as part of Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities.

Georges Seurat: Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy 1888 (Painting, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.21) Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Taking the time to look closely at a work of art is so rewarding. Having the chance to share your thoughts with another person or persons allows for the collaborative building of knowledge. #BreakForArt accomplishes these ends very well, creating an informal, online space where a group of participants (potentially spanning vast distances) can convene to share ideas. The pace of discovery and learning can be rapid if needed while still leaving a permanent record of contributions that can be returned to throughout (or at a later time). The focus on a single work for one whole hour is an opportunity for deep and careful looking (though it goes surprisingly fast). You can view the storify for this month’s conversation here.

#BreakForArt really got me thinking about the simple beauty of the conversation. It also left me wondering whether museums are currently utilizing this simple learning and engagement device to its fullest potential.

Of course, conversations are happening constantly in museums among fellow visitors, and between communities and museums as they undertake collaborative projects or educational programs. But can we say the same with respect to conversations that are casual and free-form (rather than content-creating or tour-guided)? What I particularly like about #BreakForArt is its learner-driven agenda and relative ease of access (just get online and participate).

I started wondering what it would mean to take a conversational approach to museum participation. Maybe it would mean, in addition to prompting visitors’ responses, museums would respond to the responses, offering feedback and relevant information. (Maybe this conversation could sometimes begin with the visitor’s question rather than the museum’s prompt.) Many participatory activities seem to cease with the visitor’s response, possibly ending the potential for continued engagement around that particular work, exhibition, or idea. If museums were to enter into more sustained conversations would that also provide the impetus for repeat visits/engagement?

Social media platforms such as Twitter seem to offer possibilities for reciprocal engagement between museums and users. They might also provide ways for a museum’s ‘fans’ to connect more closely with the museum’s intellectual life (see my recent post).

I think that casual, in-gallery conversations with museums are valuable too. I sometimes feel it is a shame that curatorial staff and museum administrators are rarely available to visitors during a casual visit (and outside formal education programs). I am always excited when I encounter visitor services staff who are visibly available and willing to chat in the gallery. I sometimes wish that this were a staple of the museum experience, but perhaps that’s just me. I wonder if ‘Come talk to me’ nametags worn by museum staff would be a way to prompt in-gallery conversations with staff as they are passing through.

The best thing about visiting The Umbrella Cover Museum (Peaks Island, Maine) was chatting (the singing was less up my alley, but memorable) with Director and Curator, Nancy 3. Hoffman—a most personal and conversational way to interpret the quirky collection.

In a recent post, Brad Larson proposed the ‘exhibits/events model’ as a promising next step for museums wanting to create experiences that are memorable, conversational, and more socially integral. He offered the example of the NEMA Popup Museum, reporting that the event provided an incredible platform for enriching conversations between and among staff and visitors. (I am excited by Brad’s posts so if anyone knows of related resources or events, please point me towards them.)

Alli Burness pondered the importance of museum response in her post, ‘Critical Response: Conversations in Museums’ on Museum in a Bottle. As a fellow museum tweeter, I related to Alli’s experience of unreciprocated attempts to engage with museums online. As she mentioned, lack of resources may be a factor. This is understandable, though still a missed opportunity in my opinion. Interacting directly with individuals is standard practice in the human services field. Should museums better integrate the practice into their paradigm? Alli’s question, ‘should we instead prioritize response and conversation over sharing more content?’ was thought-provoking for me (Alli Burness, Museum in a Bottle).

An interesting article by Kevin Coffee (2013) also got me thinking about the potential of the comment book in visitor discussions, and made me wonder whether museum comment books are under-utilized as conversational resources. Lately, I have become slightly addicted to reading the visitor comment book when I visit a museum; in some cases, I read them cover to cover. They are filled with incredible observations, personal stories, and unique personal connections. Sometimes, they contain interesting critiques and challenges to the museum’s authority. I am curious about how these comment books are used by museums. I wonder whether some visitors would relish the invitation to leave an email address or Twitter username so that the museum could respond directly to their comments, particularly the critical or provocative ones, which might otherwise go unacknowledged and unexplored. Coffee (2013) helped contextualize my thinking here.

I suggest that receiving feedback on our cultural participation is a powerful source of wellness and connectedness. Perhaps it is one of the fundamental reasons that we find social media so rewarding. If nobody ever liked, shared, favorited, retweeted, or commented on our posts many of us would ultimately lose interest in posting (just a point on human nature, and not a plea for comments on the blog). A response provides evidence that we are heard and helps us to know that our contribution is valued.

Responding effectively, however, may require skillful listening (whether in-person or online). This is something that social workers and community development professionals are reasonably comfortable with. How about museum professionals? I reflected a little on my experiences responding to clients from my time in human services and was able to articulate two considerations (phrased as questions to ask yourself) that particularly helped me to connect with others’ comments:

1. Can you hear not just what someone is saying, but how it relates to who they are?

2. Do you notice traces of intensity (excitement, confusion, realization, disappointment) in a person’s comment? These might be important clues and signposts to a person’s experience.

These are merely ideas to continue a dialogue about conversation with museums. Foremost, I am wondering if simply eliciting participation is enough. Or should museums consider finding ways to respond to participatory efforts, validating the important intellectual stretching and emotional risk-taking of the participants, and entering into reciprocal exchanges that could increase wellbeing, learning, and connectedness? How would museums find the time and resources to respond on an individual level, and is it feasible for all museums? What is the possible role of digital engagement in sustaining conversations and facilitating responses?

If you’re curious about what a museum-visitor conversation could look like, you could tune in to the next #BreakForArt on Monday, January 5 at 1pm EST.

Reference

Coffee, K. (2013). Visitor comments as dialogue. Curator: The Museum Journal, 56(2), 163-167. doi: 10.1111/cura.12017